The triple-deficit nation at the crossroads in 2011

The steady and substantial decline of the US dollar against most major currencies over the last 8 years is no accident. It is the result of a nation suffering from the triple deficit syndrome.

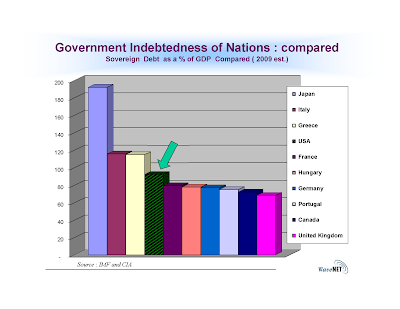

First, there is the public deficit resulting from budgetary shortfalls with our governments, whether federal, state or local. Estimated to exceed a disturbing 10% of the GDP in 2010 alone, the cumulative US Public Debt is now poised to surpass 90% of the GDP, including the still escalating liabilities in US Social Security and Medicare. Going above 100% is typically considered “high-risk” by the IMF for its potential to destabilize the sovereignty of nations.

Then, there is the trade deficit which stems from our imports dwarfing our exports. Now, that one is truly puzzling because, in theory, a depreciating currency should have made our exports a lot more attractive and help eliminate our trade imbalance. Not in our case: the Commerce Department reports that the US trade deficit is still projected to exceed 4 % of the GDP in 2010. These trade deficits, benign in the early 90’s, cumulated to exceed 60% of the GDP since then.

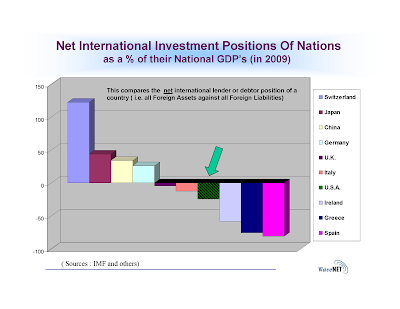

Finally, there is the current account deficit which measures the international flow of money resulting from trade and investments. Year over year, it feeds the NIIP (Net International Investment Position) to provide an indication of a country’s international standing. No good news there either : based on official 2009 data, America switched from being world’s largest net creditor in 1980 with 11% of its GDP invested internationally to becoming world’s largest debtor nation, with 25% of its GDP borrowed from other nations, notably China and Japan.

Finally, there is the current account deficit which measures the international flow of money resulting from trade and investments. Year over year, it feeds the NIIP (Net International Investment Position) to provide an indication of a country’s international standing. No good news there either : based on official 2009 data, America switched from being world’s largest net creditor in 1980 with 11% of its GDP invested internationally to becoming world’s largest debtor nation, with 25% of its GDP borrowed from other nations, notably China and Japan.Countries with large negative NIIPs face the prospect of more wealth transfer to other nations just to service their debt, let alone finance their growth. Not a comfortable position to be in.

A few percentage points of the GDP leaking over here, a few more over there, it all adds up: the American economy must now grow well above the average of the last 30 years to compensate. A daunting task considering that globalization has now introduced unprecedented challenges.

As an example of how globalization has altered the predictability of conventional thinking consider this: despite a 40% decline in the value of the dollar against the euro over the last six years, its impact on trade has been inconsequential. The total US trade deficit was still stuck at a stubborn 4 to 6% of the GDP during that entire interval, demonstrating the complex interplays in a global economy where imports and exports depend on many things, not just pricing.

So, how did we become a “triple deficit nation” with a currency in chronic decline? Was the dollar sacrificed or, was its decline simply caused by grossly dissonant economic policies?

After all, realizing that in the history of civilization no country ever sustained greatness on the back of a persistently weak currency, what was the Administration thinking all these years?

Moris Simson, former high-tech executive who now heads a strategy consultancy, is a fellow of the IC² Institute at the University of Texas