Following the third anniversary last week of Lehman’s calamitous bankruptcy, it is disheartening to see that most banks, central banks and governments on both sides of the Atlantic have failed to draw the most important lesson: financial crises cannot be controlled by increasing bank capitalizations alone if they are rooted in systemic deficiencies. We hear a lot about systemic risk from pundits and regulators, but not enough on systemic deficiency which is the root cause for the systemic risk to exist in the first place.

I define systemic deficiency as the inability to successfully react and adapt to a disruptive change in one’s environment. Extreme variations in temperature for example are known to cause certain plants to die because they cannot adapt to the disruptions. In the medical domain, another analogy is the immune deficiency syndrome. It is not only a systemic failure to recover, but is also contagious -- ironically, as is the case with interconnected global finance -- when in close contact. Furthermore, it cannot be cured with better nutrition, no more than a tropical plant can survive in the Arctic winter with increased irrigation, or an unstable banking system can outlast capital shortfalls.

I propose that we consider systemic deficiencies in banking as well. Overleveraging is the first symptom that comes to mind. That in the thick of the panic of 2008, certain banks in Europe were carrying assets 80 times larger than their equity capital ( vs. 10 to 12 as the historical norm) illustrates the extent to which balance sheet deformities had morphed into insurmountable obstacles. But there are others. My favorite one, because it is still the most controversial, revolves around financial supermarkets.

In the spotlight here is the notion of Universal Banking (as the Europeans call it) or Bank Holding Companies (as the Americans call them) allowing financial conglomerates to combine all sorts of banking services with a vast array of risk profiles, thinking that it is just a supermarket of sorts. That notion is dangerously misleading.

A supermarket is not allowed to sell firearms or toxic specialty chemicals for a simple reason: the collateral risks outweigh the economic benefits of sharing their distribution costs, not to mention that it would pose innumerable regulatory oversight problems. It would be so much simpler to designate specialty stores which can be better monitored for compliance and enforcement when the products involved carry the risk of misuse or abuse. The systemic deficiency here comes from trying to combine businesses with vastly different characteristics.

Why should finance be different? Products like stock derivatives and currency futures also carry elevated risks for misuse or abuse ( both by the client and by the supplier, as both the 2008 Société Générale and last week’s UBS debacles illustrate) and, as such, don’t justify commonality in the funding of their procurement, sales, distribution and management oversight relative to conventional banking.

Simply put, I believe that combining the deposit-driven, highly-regulated retail banking business with the equity-driven, challenging-to-regulate investment banking business produces a systemic deficiency, especially when operating as a transnational company with unavoidable cross-subsidies. The two “business cultures” are simply too incompatible to manage by the same management team without, at some point, imperiling the whole. And when the whole is too big and too interconnected, the contagion risk to endanger most if not all of the others is too big a risk to assume for any society, no matter how daring.

To be sure, the trajectories to financial supermarkets have been historically quite different on both sides of the Atlantic. In the US, up until 1999, the Glass Steagall legislation barred in the preceding 66 years cross-ownership of banks, securities firms, and insurance companies. That explicit legal separation between commercial banking and investment banking served the US well -- and the world -- all these years, providing for a prolonged era of stability fueling the post-WW2 economic expansion.

In Europe, by contrast, retail, commercial and investment banking were usually carried out together by large and established banks that saw their roles as one-stop supermarkets capable of delivering a vast array of financial services. In countries like Germany, U.K., France and Switzerland, the Universal Bank notion had always been the guiding principle for combining all sorts of financial services leading to concentrated economic power in the hands of a handful of large banks. Things worked out well until two discontinuities emerge and insidiously shook the business model at its foundation to create systemic deficiencies.

1. First was the love affair with equities. As equities became more in vogue for a traditionally conservative European consumer, so did the volume of stock underwriting, derivatives trading and other market-making for the European banks. Moving rapidly from the time-tested, comparatively stable consumer and corporate lending business to the higher-risk, higher-volatility world of equities --and derivatives-- was bound to change the nature and predictability of the banking business. (And change it did, across both sides of the Atlantic.)

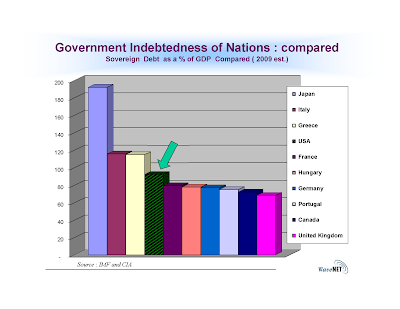

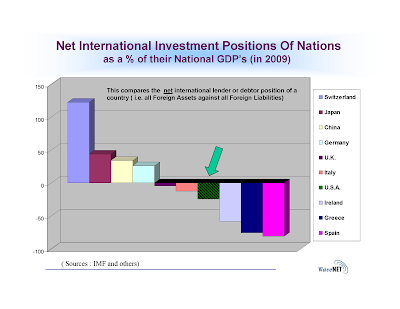

2. Second, was the formation of the EU with a unified currency but with disparate legislations in the financial sector. As long as banking practices and regulations were managed by separate governments, that there would be over time bothersome differences emerge among members of the Eurozone could not have been a surprise. Even more important was the dissonance in fiscal policy: there was no shared “song sheet” on how governments intended to balance their public debt. A unified currency in a dissonant and unenforceable environment of fiscal discipline has now unequivocally proven to be a foolish experiment for testing the resiliency of banks, central banks and the sovereign countries that harbored them.

Three years after the Lehman implosion which saw over $30 trillions of wealth temporarily vanish inexplicably worldwide by March 2009, the eruption of the sovereign debt crises in Europe raises an unavoidable question: is Western World banking threatened to the core? As the globe waits impatiently for an answer, three remedial approaches are noteworthy.

· First is America’s financial reform under Dodd-Frank which grappled with the too-big-to-fail problem but succumbed to lobbyist pressures without really providing the needed clarity for actionable specificity. A notable exception is the “Volcker Rule” (named after the famous former Fed governor) which severely curtails a conglomerate’s ability to own entities that engage in unrestricted and lightly regulated activities -- such as hedge funds or private equity funds –- and also prohibits proprietary trading which exposes all ordinary shareholders to an inordinate level of undesirable risk.

As of this writing, it was disconcerting to see that there was still considerable political resistance for the adoption of the Volcker Rule in a timely fashion, if at all, confirming my fear that the most important lesson from the 2008 financial meltdown fell on deaf ears.

· Second is the Basel 3 deliberations to drastically tighten capitalization levels on all banks by 2019 but without addressing neither the source of funds (estimated to exceed $1 Trillion while being highly dilutive to existing shareholders) nor how would that address the above two discontinuities posing systemic instabilities. Basel 3 is a classic example of addressing the “are we doing it right?” question without first asking “is this the right thing to do?”

· Third -- and this is a big surprise -- is the approach in Britain to universal banking. In September 2011, the independent commission advising the U.K. government ended up recommending the structural separation between commercial and investment banking. Although it stopped short of a complete legal separation as in Glass Steagall, the “ring-fencing” of retail banking with the purpose of insulating it from external shocks clearly underscores their recognition of the inevitable need for structural reforms.

It is ironic that the systemic deficiency warning came from the country where banking is relatively the most concentrated in the world, and where too-big-to-fail is almost a euphemism for too-big-to-save. But, hey, why shoot the messenger? Finally one country has discovered that what I call the OMO Principle (for opacity, mendacity and obstinacy) in banking is self-destructive.

The British, in a totally understandable move of self-preservation, are pointing the way to the rest of Western banks that perhaps Glass Steagall wasn’t bad after all. The French have even a saying to denote the nostalgic impulse for humans to gravitate towards the well-understood: “plus cela change, plus c’est la meme chose.”

Could this be a new beginning?